Yoga has meant different things to different people throughout its history. It’s evolved and involved to meet the unique and changing needs of its times. Yoga continues to transform and adapt through the perspectives of its practitioners. Despite yoga’s ongoing evolution, certain key threads of have been woven into its complex harmony, distinguishing it from other traditions.

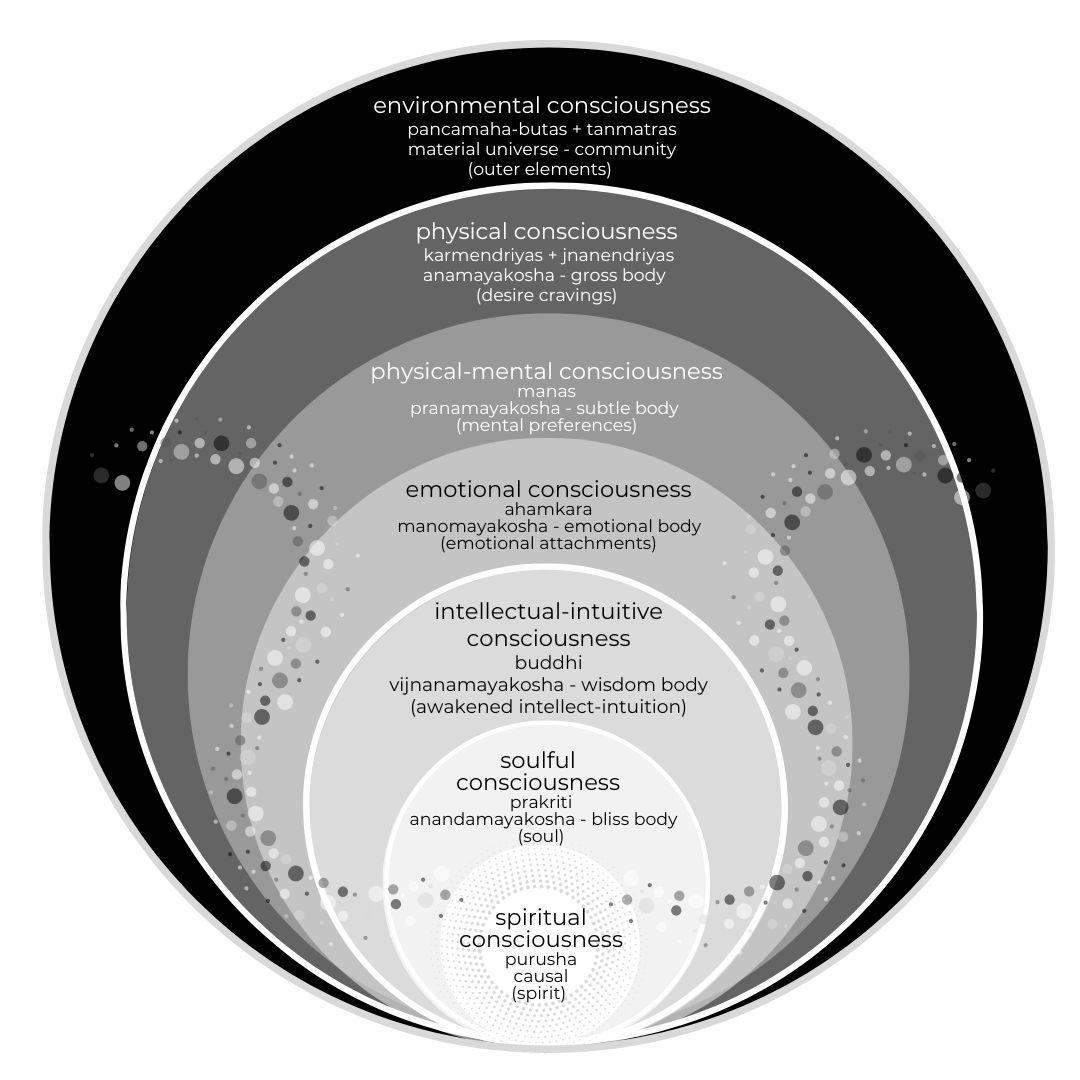

Numerous ancient texts refer to the Sanskrit term “yoga” (योग) as a state of being – a state of unity consciousness and no-self. Central to this state is a sense of abiding in essence nature and merging with the cosmos. In this context, yoga is not a practice or process, but rather a way of existing – a super conscious state of connectedness. It is the experience of full aliveness that happens when we are intimate with reality itself. It results in freedom from the illusory notion of who we are as a small, separate self and the suffering caused by that belief.

In addition to being a superconscious state of connectedness, yoga is also defined a collection of multi-faceted practices that support the arising of that unitive experience. Yoga as a method cultivates favorable conditions for yoga as a state of being to occur. Although yoga practices vary in technique, they share the same purpose of helping us transcend the illusory notion of separateness and the confusion inherent in that limited perspective. The texts of non-dual Shaivism and the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali share rich traditions designed to help us inhabit a super conscious state of connectedness. These perennial yoga practices are commonly referred to as angas (अङ्ग), a term that may be translated from Sanskrit to English to mean supports or limbs. The eight historical supports that collectively distinguish yoga from other traditions are:

yamas-niyamas (collective ethics and personal integrity),

asana (experiencing and influencing gross energy),

pranayama (experiencing and influencing subtle energy),

pratyahara (withdrawing the senses inward),

dharana (concentrating on fundamental realities),

dhyana (meditating on everythingness and nothingness), and

samadhi (spontaneous merging of the finite with the infinite).

These supports invite us to move out of our conditioned, habitual body-mind cycles and protection-seeking ego patterns and move into a clear and loving recognition of “what is.” A “what is” that not only includes increasing sensitivity to our physical, mental, and emotional experience, but also to the indivisible interconnectedness of everyone and everything.

Practiced in sequence, these supports serve as a progressive path, each naturally flowing from the previous practice and incrementally emphasizing more subtle awareness of what is. Observing collective and personal ethics through the yamas and niyamas sensitizes us to the whole of life and its fundamental mutuality, without which the fruits of the other yoga practices fade away. Asana practice attunes us to gross sensations of our physical body and prepares us for morenuanced energetic awareness of pranayama practice. Pranayama hones our ability to experience and influence subtle energy which prepares us to more refined awareness of even subtler energy experiencing as we withdrawal our senses inward in pratyahara practice. Multi-form practice of the yamas, niyamas, asana, pranayama, and pratyahara grow our receptiveness to the sublimity of concentration in dharana and etherealness of meditation in dhyana. Our increased ability to repose in the subtlest states of concentration and meditation opens us to the most subtle and immersive experience of samadhi.

While these practices naturally unfold from each other, they also develop simultaneously and overlap with each other. Practicing one support of yoga nurtures the other supports. As an interconnected web of influence they are each an integral composite part of the whole of yoga. Engagement with multiple aspects simultaneously increases the potential for development in all the practices and a radical loosening of our identification with our body-mind selves.

Yoga is samadhi-centric. The seven other supports of yoga revolve around samadhi and hold the potential to move us toward the samadhi center where we experience ourselves and all of life as a dynamic continuum of consciousness beyond the distinction of subject and object. The samadhi core is where consciousness spontaneously experiencesitself in an ever-changing field of possibility uncaged by the body-mind.

The supports surrounding samadhi can be grouped in a couple of ways. One configuration is as outer and inner supports – with the yamas-niyamas, asana, and pranayama emphasizing the most gross forms of experience - and pratyahara, dharana, and dhyana emphasizing the subtlest forms of experience. Another way the supports organize around samadhi is as bhukti-centered supports emphasizing pleasure and mukti-centered supports emphasizing liberation. Asana, pranayama, and pratyahara all are particularly conducive for experiencing bhukti, and the yamas-niyamas, dharana, and dhyana are all particularly conducive for experiencing mukti.

An asana-centered concept of yoga is a modern and misinformed idea about what yoga really is and does. Alienating asana from the other supports cuts into yoga’s totality and potential so severely that it can actually reinforce egoic conditioning and a sense of separateness. Yet too often, asana fundamentalism dominates mainstream yoga practice - with emphasis on idolized alignment, perfect sequencing, and all variations and manifestations of body-based pretentiousness. This kind of asana zealotry - and all the ego-driven power play that goes along with it - can really blind us to the bigness that yoga really is.